You might remember how earlier this month when a senior editor from Kotaku named Alyssa Mercante wrote the following on Twitter/X in response to a criticism of a story she wrote:

hi! you can't be racist against white people! thanks for tuning in!

— Alyssa Mercante, former cam girl (@alyssa_merc) March 6, 2024

Today, I wanted to present to you a longish piece exposing a hidden, awful (and wrong) assumption embedded in those claims that black people can’t be racist.

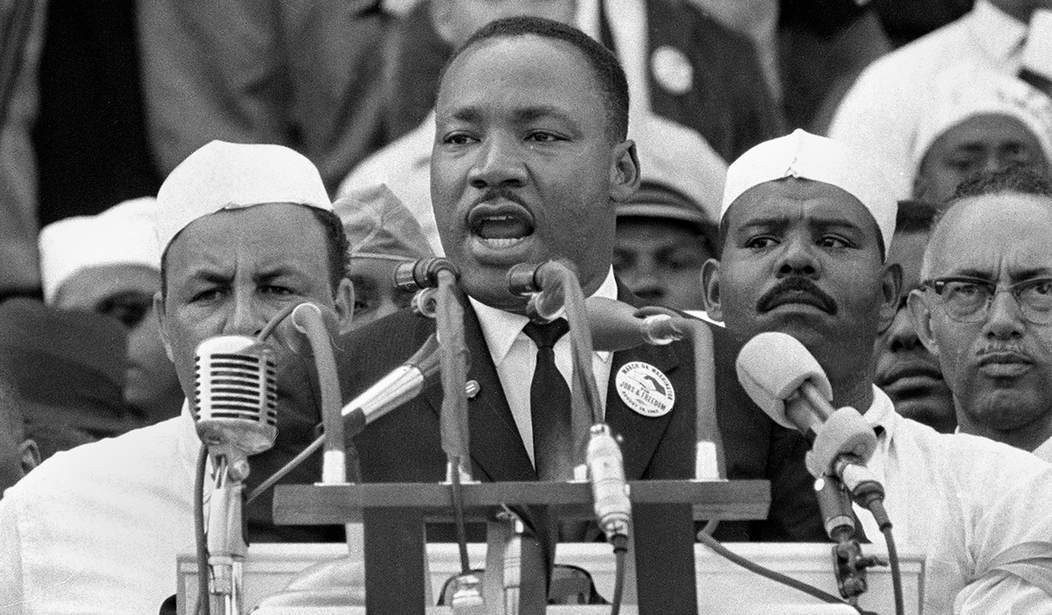

For myself, I have always defined racism as nothing more than the opposite of Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s ‘dream.’ Naturally, I am referring to one of the most famous lines in any of his speeches:

I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.

Thus, my definition of racism is where a person is not judged by the content of their character but by the color of their skin.

But, of course, the left doesn’t want us to follow that definition of racism, because then that would force them to admit that black people and other people who are racial minorities in America can be racist and white people can be victims of racism. You have to understand that to many on the left, whether or not you are a racist is based on color of your skin, not the content of your character.

But to dress it up as something other than a betrayal of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s ‘dream,’ they often try add a bunch of nonsense about power to the definition. This article …

Where Did We Get the Idea That Only White People Can Be Racist? by Peter Wood | NAS https://t.co/DaLu1c4bbZ

— MamaMcBear (@mamamcbear1) August 11, 2021

… discusses this kind of claim, writing that the University of Delaware had adopted this definition of racism on its campus:

A RACIST: A racist is one who is both privileged and socialized on the basis of race by a white supremacist (racist) system. ‘The term applies to all white people (i.e., people of European descent) living in the United States, regardless of class, gender, religion, culture or sexuality. By this definition, people of color cannot be racists, because as peoples within the U.S. system, they do not have the power to back up their prejudices, hostilities, or acts of discrimination….’

You get it? Racism requires power, and because nonwhites have no power, they can’t be racist—or so the argument goes. The hilarious thing is I first heard this claim deep in the Obama years—when literally the most powerful man in America was a black man. So, when one person made that argument to me, I made this incredulous response:

So Obama has no power? @AllisonGranted @SallyStrange

— (((Aaron Walker))) (@AaronWorthing) December 24, 2014

In another conversation, a person claimed that somehow Obama literally had no power even though he was president, because he was black. I mocked that claim ruthlessly by saying that if he actually believed that, then that would be an argument against electing a black president because we need a president who has actual power. I mean, that is where that dumb logic leads.

But hidden underneath that is the claim that black people have no power. As in zero.

That claim is facially ridiculous, especially today, but I want to expose how that thought is also a slander on the human spirit. Allow me to explain why I am saying this.

It would be hard to argue that there was any time in American history where black people had less power, than during slavery, right?

But did they have zero power? As in none at all?

No.

It is a truism that throughout history when people are oppressed, they always find ways to fight back. One obvious way is rebellion, and there were several slave revolts in American history. Further, slaves could escape. Some successfully made their way all the way to free states. Some kept running until they made it Canada. Others were too deep in the South to make it that far—a slave fleeing a plantation in Alabama was never going to make it to the free states. Slaves in that situation would often find a bit of woods or swampland nearby and live off the land. It was often a meager existence, but they felt it beat living on a plantation and ... well ... they would know better than I would.

But besides those active and open acts of defiance, American slaves also engaged in what historians call ‘passive resistance.’ Historians often called it ‘fooling old master’ although it was usually written in a questionable imitation of slave talk which I am avoiding. However you want to write it, it amounted to this: The slaves would intentionally work slowly, break equipment when the master or overseer isn’t looking and do similar things, to gum up the works so that less work was done and they didn’t have to work themselves so hard. It’s virtually identical to the tactics seen in the Soviet Union when workers passively resisted that system, described generally under the saying ‘you pretend to pay us, we pretend to work.’ And it is probably where the stereotype that black people were lazy came from—as if a person is being ‘lazy’ when they don't enthusiastically work when they are forced to against their will.

How successful were these various forms of resistance? So much so that I have long argued that the Emancipation Proclamation was the turning point of the Civil War.

Prior to the Proclamation, Lincoln had decided to try to win the Civil War by attempting to reach out to loyal white plantation owners and when Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, it represented his decision to instead ally with the slaves, free black people and anyone else who wanted a war of emancipation. To make this point, I am going to quote an absolutely brilliant writer: Myself. Jokes aside, in a piece I wrote in law school, I discussed the clash between President Lincoln and Representative Thaddeus Stevens on slavery policy during the Civil War:

At the beginning of the war, Lincoln attempted to remain ‘neutral’ on the issue of slavery. No slaves would be freed, no black troops would be employed, and Northern armies would expend their valuable resources to capture and return slaves to their masters, even if the master was a Confederate.

As an aside, consider how ridiculous that last point is. Ordinarily if a 19th century army is going through enemy territory, they might or might not forage or otherwise take resources from the local civilian populace. But even if they are not actively stealing from the local populace, if they see a bunch of horses or cattle belonging to enemy civilians break through their fences and run away, most of the time they wouldn’t lift a finger to retrieve them. But, suddenly, when human beings are trying to escape, Northern troops would actually waste their time trying to retrieve them.

Back to quoting myself:

Stevens viewed the policy as both immoral and inefficient. Its immorality was demonstrated by sickening reports of slaves attempting to escape, only to be shot by Union soldiers as they fled. The policy’s inefficiency was proven by the fact, acknowledged by no less than Jefferson Davis, that slavery was the secret weapon of the Confederacy. First, it freed white manpower, allowing young slaveholders to leave their plantations. Second, as many as one in five slaves worked in direct support of the war effort; some prepared war materials, while others worked as auxiliaries to the Confederate army, performing duties that were performed by soldiers in the Union army, such as fortification, engineering and supply. All of this was only possible because of Lincoln’s ‘neutral’ stance on slavery. The slaves had no reason to take any interest in Northern victory, because no matter which side won, their servitude would continue.

Stevens recognized the centrality of slavery to the Southern war effort. ‘Although the black man never lifts a weapon,’ Stevens declared, ‘he is really the mainstay of the war.’ Stevens, therefore, had a simple prescription: employ the slave in the cause against the Confederacy. ‘[T]he natural enemies of the slaveholders, must be made our allies.’ Therefore the slaves must be emancipated. That alone, Stevens understood, would strike a death-blow to the Confederacy. Unlike many Northerners, Stevens understood that the slaves followed Northern policy closely, through the ‘grapevine telegraph’ [that was Lincoln’s term] and, even if they did not actually abandon their plantations, they would bring the Southern economy to its knees by passive resistance. Subsequent events bore him out. As Jeffrey Hummel points out, ‘[l]iberation, so often presented as something the Union did for blacks, was as much something they did for themselves.’

(Footnotes omitted. All of that is from: Walker, Aaron J. ‘‘No Distinction Would Be Tolerated': Thaddeus Stevens, Disability, and the Original Intent of the Equal Protection Clause.’ Yale Law & Policy Review 19, no. 1 (2000): 265-301.)

Now, obviously it is impossible to prove that the Emancipation Proclamation was actually the turning point of the war. After all, it was a question of how long the South could hold out, and so anything that degraded their military or economy, or increased the power of the Union, could be argued to be the turning point of the war. Thus, I could never prove that the South would have won but for the Emancipation Proclamation, but in my gut, I believe the moment it was issued, the Confederacy had little chance of victory. Take that for what you will.

Regardless of that, that passage I just quoted from was focusing on the power struggle between Abraham Lincoln and Thaddeus Stevens, but it also makes an important and affirming point. The slave was not powerless. The slave could still find ways to snatch power away from their masters. The people always find power even when their official power was slight.

So, to say something like ‘black people can’t be racist because black people have no power’ is a slander on the human spirit. Black people as a group have never been completely powerless in American history; They were too intelligent, too clever, to let that happen to them. And the same can be said of all peoples, of all races, in all times, throughout our history—not just those enslaved, but those oppressed by other means. Some of them revolted, some of them escaped, and some of them engaged in passive resistance, but they all found ways to steal power they weren’t supposed to have for themselves. Because our greatest power is in our spirits, our universal yearning for freedom that cannot truly be suppressed, and our ingenuity in finding those techniques of resistance.

And it is that universal spirit in humanity that these defenders of racism have to pretend did not exist.

Of course, we all know what is really going on, anyway. The Greeks called this fallacy ‘Special Pleading.’ But in the process of trying to push that fallacious claim, they had denied and denigrated the power of the human soul to resist oppression. It reduces black people in America to being nothing more than passive victims of history, instead of people who could find power and exert control over their destiny when things surely looked their bleakest.

Rather than denigrating or ignoring that strength of spirit, it should be celebrated.