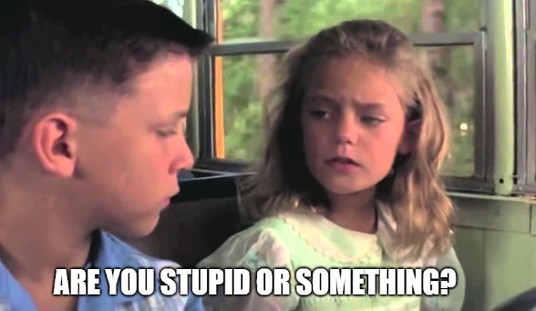

Welp, believe it or not, after failing to win a seat in the House of Representatives, Cenk Uygur now wants to attempt to be President of the United States. Yes, really:

Yes, I'm running against Joe Biden for the Democratic nomination. Joe Biden is down 24 points on the economy. He has no ability to make up that kind of ground on the most important issue. We need a new candidate now! https://t.co/JdRkmvU9Cy

— Cenk Uygur (@cenkuygur) October 12, 2023

I mean, there is failing upward and then there is whatever Uygur is attempting to do, here.

Cards on the table, I meant to cover this at the time he first announced but life and other work intervened. But Cenk is in the news again after getting absolutely slapped around by Douglas Murray, and that is exactly the thin excuse that I need, to talk about this again. And, besides, this gives me the chance to nerd out on various Constitutional issues you might or might not know about, even if you aren’t very interested in who is qualified to be president of the United States.

Besides, this is the season of giving and I am giving you the gift of knowing that this weirdo will never be president. I’m a giver that way. A giver, I tell you.

Of course, one reason he will never be president might be because he is weirdly okay with bestiality. Yes, really:

BREAKING: #Cenk2020 calls for legalizing BESTIALITY where you "are pleasuring the animal" in 2013. (Warning: Explicit Video)

— Receipt Maven (@receiptmaven) November 26, 2019

Even TYT folks are like say "WHAT"???@peta @spcaLA #CA25 #NeverCenk #SexualAssaultOfAnimalsIsACrime pic.twitter.com/uc6hTAn7Ww

Neigh means neigh, Cenk.

But that’s not the reason why he definitely never would be president. Nor is his pretty antisemitic view of the current war between Israel and Hamass:

I'm only presidential candidate on either side who would cut off all funding to Israel until it ends this war, ends the occupation and signs a peace deal guaranteeing a Palestinian state. Send at least $1 to my campaign so that others will follow my lead: https://t.co/E34SDYudoV

— Cenk Uygur (@cenkuygur) December 19, 2023

How upside down is that logic, anyway? It’s like saying America needed to end the war with Japan on December 9, 1941. Israel is only at war because Hamass has chosen to wage it. To quote Will Smith in the original Men in Black: "Don't start nothing, won't be nothing!" Before the attack on October 7, there was a ceasefire and Hamass broke it. In fact, even after the current war broke out, there was a brief ceasefire. I think they officially called it a pause, but that’s what it was: A ceasefire. And Hamass broke that, too. So, it is not even possible for Israel to end this war, short of surrendering and letting Hamass kill and rape even more of its citizens.

And in all frankness, they shouldn’t stop until Hamass is obliterated.

That kind of moral inversion can only be explained by extreme antisemitism. The fact that he doesn’t care nearly as much about Uighurs in China who are literally in concentration camps (as Murray points out) only cements it. He hates Israel because it is full of jooooooooooos! Other people might criticize Israel for unbigoted reasons, but he is not one of those people.

But that’s not why he can’t be president. For many on the left, antisemitism is a feature and not a bug.

No, that isn’t what I am talking about. I am talking about the fact that Cenk Uygur is not a natural-born citizen.

The Constitution doesn’t put many limitations on who can be president, but one of them is that he or she has to be a naturally-born citizen. As it says in Article II, Section 1:

No Person except a natural born Citizen, or a Citizen of the United States, at the time of the Adoption of this Constitution, shall be eligible to the Office of President[.]

It goes on to list age and residency requirements and disqualifications that exist in other parts, but that is the part I am focusing on.

It is worth noting that it contains a giant exception for those who were citizens of the United States at the time of the adoption of the Constitution. I jokingly call it the Hamilton exception because it was plainly designed to make people like Alexander Hamilton eligible. Maybe they were even thinking of him specifically. He was born in the Caribbean colony of Nevis, and thus would not be a naturally born citizen, but the founders agreed that people like him who literally fought to free this country from Britain should be eligible to be president.

But Uygur is around 200 years too late to enjoy that exception, and he was born in Turkey. The show called The Young Turks (invoking the name of a political movement involved in the Armenian Genocide) is called that for a reason. So how does he get around that constitutional language?

Well, you see, he plans to sue to get on the ballot, and he think the case law is clear, despite the Constitution being pretty darn clearly against him.

Case law is clear. Naturalized citizens can run for President: "Schneider is clear that treating natural born citizens and naturalized citizens differently is contrary to the Fifth Amendment. Forbidding naturalized citizens from being president or vice president is a form of…

— Cenk Uygur (@cenkuygur) October 12, 2023

Winning this case in the Supreme Court is going to get rid of the albtatross around the neck of 25 million Americans who are naturalized citizens. The Supreme Court has already said we have the same exact rights. https://t.co/JdRkmvU9Cy

— Cenk Uygur (@cenkuygur) October 12, 2023

Now, this is a case where Community Notes comes up short. They are sort of right, but it's more accidentally right than anything else, like the proverbial broken clock being right two times a day. Community Notes needs to be reformed and the first place to start is that Wikipedia is never a valid source for the law. The law comes from things like the Constitution, from statutes and from case law. I would go as far as to say that maybe Community Notes should institute a rule that says that only lawyers can write them—or at least requiring a lawyer’s approval. This is the second time I caught them using non-legal sources in a Community Note, the last time being when they got things absolutely wrong in relation to Robert Kennedy Jr.’s eligibility for Secret Service protection.

So, let’s look at what the Community Note said:

Schneider v. Rusk hasn't been recognized or upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court or any other authoritative legal body in the context of naturalized citizens running for President.

That would be Schneider v. Rusk, 377 U.S. 163 (1964) and any lawyer among our readers is already seeing the problem right from the citation I gave you. Schneider is a Supreme Court case as indicated by the "U.S." part of the citation. So, there is no need for the Supreme Court to uphold it. It is good law until it is overturned.

I think what they meant to say is that the Supreme Court has not applied Schneider in the context of naturalized citizens running for president. In fact, the Supreme Court is pretty explicit in saying Schneider does not apply in that circumstance.

But to explain that, I have to dig a little deeper and talk about a little-noticed bit of constitutional bullsh-t. I have to go back to May 17,1954, to the day that Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) was decided. Under Brown, the Supreme Court held that the Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause meant that, at least in the context of state-run education, separate can never be equal.

(Mind you, while Brown made it sound like they were only talking about education, it was effectively the end of legalized government segregation. The Supreme Court never upheld segregation by government again.)

That’s not the constitutional B.S. I am referring to. Brown was, in my opinion, correctly decided as a matter of the original intent of the framers. One of my Constitutional heroes, Thaddeus Stevens, said when he introduced his first draft of the Equal Protection Clause, that it was his dream ‘that no distinction would be tolerated in this purified Republic but what arose from merit and conduct.’ The Supreme Court could have simply said that when you separate white and non-white students from each other, you are drawing a distinction between them that is not based on merit or conduct and be done with it.

Instead, the Supreme Court cited studies that showed that segregation was harmful, psychologically, to black children. This was minor constitutional B.S. but it allowed them to do two things simultaneously. First, it allowed them to pretend that the Supreme Court was never wrong on the law in Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896), they just didn’t understand the fact of this psychological impact. That allows for a little institutional face-saving that they didn't deserve.

Second, it allows them to avoid citing what the actual founders of the Fourteenth Amendment said. You might have no idea how deeply hated Thaddeus Stevens and the other founders of the Fourteenth Amendment were in the South in 1954. As I previously mentioned, a thinly-veiled fictionalization of Stevens was the villain of the early silent-film epic Birth of a Nation. If the Supreme Court had said they were not only desegregating the schools but they were doing so based on the values of Thad Stevens and the other Republicans who got the Fourteenth Amendment made into law, we might have seen a second civil war break out. The fight for desegregation was contentious enough as it was. So that is constitutional B.S. but it is essentially harmless—reaching the correct result, but maybe not being entirely honest about why.

No, the real constitutional B.S. comes from another case decided the same day as Brown: Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497 (1954). Eagle-eyed readers might have noticed that when I discussed Brown, I mentioned that it applied to state-run education. So, you might reasonably have guessed that this didn’t apply to wholly private schools … or schools run by the Federal Government.

You know, like in Washington, D.C. or other federal territories.

And in 1954, Washington schools were segregated, and the Supreme Court faced the prospect of creating a situation where there were still legally segregated government schools in our capital. This not only presented a moral problem but even a diplomatic problem. We might be trying to convince the diplomat of an African country to resist communism in a city where he has to go to a ‘colored’ restroom.

So, the Supreme Court engaged in a little B.S. in Bolling. As you might recall, Section One of the Fourteenth Amendment says this:

All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

You notice that the last two clauses are the Due Process Clause (of the Fourteenth Amendment) and the Equal Protection Clause.

Meanwhile the Fifth Amendment to the Constitution says this:

No person shall be held to answer for a capital, or otherwise infamous crime, unless on a presentment or indictment of a Grand Jury, except in cases arising in the land or naval forces, or in the Militia, when in actual service in time of War or public danger; nor shall any person be subject for the same offence to be twice put in jeopardy of life or limb; nor shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself, nor be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation.

So, there is a due process clause, but noticeably no equal protection clause.

But, the Supreme Court said, the truth is that the concept of due process includes the concept of equal protection. And, therefore, the Supreme Court invented, out of whole cloth, what is called ‘the equal protection component of the due process clause of the Fifth Amendment.’

It’s B.S. Like it or hate it, it is B.S. And based on that B.S. the Supreme Court said that D.C.’s schools had to be desegregated, too.

In fact, since then, the Supreme Court has said that the equal protection component of the Fifth Amendment is interpreted exactly like the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, which means that the Equal Protection Clause is basically a redundancy.

So, we come back to Schneider v. Rusk. In that case the Supreme Court confronted a law that said that if you were a foreign born American citizen, and you resided continually for three years in the country you originally came from, you lost your American citizenship.

The facts of the case give you a pretty good illustration how it worked. The woman was German by birth and came to America when she was 16, and became an American citizen. When she was in France for post-graduate schooling, she fell in love with a German and basically went to live with him in Germany and only returned to America to visit. But after three years of living in Germany, officials started denying her the right to enter on the basis of her no longer being a citizen and she sued to be declared one.

The Supreme Court said that this was discrimination between people who were natural born citizens versus people who were born in another country who became American citizens. For instance, if she had happened to be born in America and then did everything else the same—falling in love with a German and living in Germany ever after—she would still be a citizen. But because she was originally a German citizen, the statute took away her citizenship. And so the Supreme Court said that this discrimination violated the equal protection component of the Fifth Amendment found in Bolling, and struck it down.

And Cenk Uygur clearly thinks it is a touchdown for his argument, quoting from a law review article (essentially an academic article on the law) as saying ‘Schneider is clear that treating natural born citizens and naturalized citizens differently is contrary to the Fifth Amendment.’

That’s mostly true, but Schneider also said this:

We start from the premise that the rights of citizenship of the native born and of the naturalized person are of the same dignity and are coextensive. The only difference drawn by the Constitution is that only the ‘natural born’ citizen is eligible to be President.

In other words, the very case he mentions notes and endorses the rule he thinks suddenly is unconstitutional.

Of course, the Supreme Court can always overturn itself, but Schneider really isn’t helping Uygur. But he is also citing that law review article and I went and looked at what it had to say. And it is clever … but it is also dumb.

You see sometimes lawyers and professors like to form ‘legal theories’ almost like it’s a parlor game. I mean, this is a profession that attracts people who like to play with ideas and language, and frankly some good lawyering can come from that kind of brainstorming. And professors have to be published on a regular basis to build their résumé. So legal academia is rife with arguments that are often very clever, and would be completely laughed out of any courtroom.

And a prime example of this is the article that Uygur cites, called ‘Limiting the Presidency to Natural Born Citizens Violates Due Process’ by Paul A. Clark.

The argument works like this. Typically in law, if there is a conflict between two laws of equal stature, the newer law wins. So, for instance, if your state passes a law defining murder in 1950, but then passes a new law defining murder differently in 1970, if there is any contradiction between those two statutes, the 1970 law wins (or controls).

So, Clark argues, since the Fifth Amendment was ratified after the original Constitution, if there is any contradiction, the Fifth Amendment controls.

Then he brings right back in that equal protection component of the Fifth Amendment and says that there is a contradiction between the general command of that amendment found in Schneider that you treat natural born citizens the same as those who become citizens after immigrating here. Therefore, because there is a contradiction, the Fifth Amendment controls and foreign-born citizens like Uygur can become President of the United States.

It's all clever, but it would never actually fly.

By now you already know about one problem posed by the argument: The equal protection component of the Fifth Amendment’s Due Process Clause is not a real thing. The courts will pretend it is real, but it is not. It’s a bit of constitutional B.S., and I would argue that everyone on the Supreme Court is aware of that.

But here’s the other problem. It fundamentally misunderstands the nature of the Bill of Rights.

You see, James Madison was actually opposed to the entire idea of a Bill of Rights in the first place, because he was afraid of a concept called expressio unius, which is short for expressio unius est exclusio alterius. It is legal Latin that means that if you express one thing, you imply the exclusion of the other. It is a basic presumption in legal interpretation.

For instance, imagine that a man died and left behind his wife, Sarah, and three children—James, Sam and Laura. In his will, he said that ‘my estate will be divided evenly among Sarah, James and Laura.’ By including his wife and two of his children, the will is implying that the middle child, Sam, is excluded and gets nothing. And that is how courts will almost certainly interpret it based on that presumption, unless that presumption can be rebutted.

The first eight amendments of the Bill of Rights are a list of things that the Federal Government cannot do and Madison was afraid that if they had a list of things that the Federal Government could not do, that it would imply that everything they didn’t list was something that the Federal Government could do under the principle of expressio unius.

He eventually came around to the idea of having a Bill of Rights—being persuaded by Jefferson. But it was partially because he found a solution to the expressio unius problem. He explained his solution to his fellow founders when he introduced his draft of the Bill of Rights in Congress:

It has been objected also against a bill of rights, that, by enumerating particular exceptions to the grant of power, it would disparage those rights which were not placed in that enumeration, and it might follow by implication, that those rights which were not singled out, were intended to be assigned into the hands of the general government, and were consequently insecure. This is one of the most plausible arguments I have ever heard urged against the admission of a bill of rights into this system; but, I conceive, that may be guarded against. I have attempted it, as gentlemen may see by turning to the last clause of the 4th resolution.

I admit that is a little bit thick to read through, but when he talks about the ‘general government’ he means what we today call the U.S. or Federal Government. And what he says is that he drafted language to solve that problem. And what was that language?

Well, I won’t bore you with showing you his original version. Instead, it is essentially what became the Ninth and Tenth Amendments:

Amendment IX

The enumeration in the Constitution, of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people.

Amendment X

The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.

In short, what those amendments are actually doing is negating the principle of expressio unius. You see, very often people get their constitutional analysis backwards. When the Federal Government wants to do a thing, the first question you should ask is ‘where does the Federal Government get the power over it?’ Even the most liberal justices will admit that all powers not granted to the Federal Government are denied. They just disagree on how broad the grant of power to the Federal Government actually is.

So, for instance, I truly believe that (outside of the territories), the Federal Government has no power to ban abortion or to make it legal when a state would make it illegal, because I don’t believe that the Federal Government has been granted any power over abortion

(That doesn’t mean that there is a right to abortion in the Constitution that trumps state law, either. Instead, it truly is something left to the states.)

The fact is that the majority of the importance of the Constitution is its organization of this new Federal Government and its grant of power to that government. This especially true of the original Constitution. There are a few rights in it, but most of it is about what the government looks like and what power it has.

And what Madison was saying in that discussion is that the Bill of Rights didn’t create legal rights. The Federal Government never had the power to do anything listed in the Bill of Rights in the first place! If there was no First Amendment, for instance, the Federal Government would have no power to regulate what people said and wrote, anyway. And the same can be said about the first eight amendments, including the fifth.

So, while the Fifth Amendment came later in time than the original Constitution, it really wasn’t an amendment. It is better understood as a clarification of what powers were already denied to the Federal Government. If it never existed, the Federal Government would still be denied those powers. And to the extent that the interpretation of the Fifth Amendment contradicts the plain text of the original Constitution, that interpretation must be wrong.

I doubt the Supreme Court will ever admit that this implies that the entire concept of an equal protection component of the Fifth Amendment is nonsense, but I don’t believe they will do anything as ridiculous as abrogating the plain text of the original Constitution based on their invention.

And before anyone twists my words, this doesn’t mean I would want any racial segregation in America at any time. Segregation, slavery and even ordinary racial discrimination should never have existed for a moment on American soil—or indeed anywhere in the world. But an honest interpretation of the Constitution means that sometimes the things you wish would happen, doesn’t happen, or that things you wish couldn’t happen, could happen. I have long said that if you can’t think of some part of the Constitution—as it current operates under its amendments—that you think is wrong or at least bad policy, you are probably not interpreting it correctly. You are probably conflating ‘the Constitution’ with your personal policy preferences.

(Mind you, when I say ‘as it currently operates’ that excludes dead language such as anything recognizing slavery before the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment.)

But that means for me I would say that while the Fifth Amendment doesn’t have an equal protection clause, it should. And I would fully support an amendment bind the Federal Government to such a clause.

So, to sum things up, Cenk Uygur’s argument is based on constitutional B.S. and I don’t believe he has any chance of winning his argument.

And, to return to the main topic … while Thanksgiving is over, I happen to think Christmas is equally a time to be thankful for what you have. So let us all be thankful that, barring a constitutional amendment, Cenk Uygur can never be president. And that, my friends, might be the greatest Christmas gift of all.

To quote from A Christmas Carol: ‘A Merry Christmas to us all; God bless us, everyone!’